Social Coherence: Outcome Studies in Organizations

There are obvious benefits to interacting and working with individuals who have a high level of personal coherence. When members of any work group, sports team, family or social organization get along well there is a natural tendency toward good communication, cooperation and efficiency. Social and group coherence involves the same principles as global coherence, but in this context it refers to the alignment and harmonious order in a network of relationships among individuals who share common interests and objectives, rather than the systems within the body. The principles, however, remain the same: In a coherent team, there is freedom for the individual members to do their part and thrive while maintaining cohesion and resonance within the larger group’s intent and goals. Social coherence is therefore reflected as a stable, harmonious alignment of relationships that allows for the efficient flow and utilization of energy and communication required for optimal collective cohesion and action.[170]

When individuals are not well self-regulated or are acting in their own interests without regard to others, it generates social incoherence. Stressful or discordant conditions in a given group act to increase emotional stress among its members and can lead to social pathologies such as violence, abuse, inefficacy, increased errors, etc.[318] It has become increasingly clear that the leading sources of stress for adults are money issues and the social environment at work. More than 9 in 10 adults believe that stress can contribute to the development of major illnesses such as heart disease, depression and obesity, and that some types of stress can trigger heart attacks and arrhythmias. While awareness about the impact stress can have on emotional and physical health seems to be present, many working Americans continue to report symptoms of stress with 42% reporting irritability or anger, 37% fatigue, 35% a lack of interest, motivation or energy, 32% headaches and 24% upset stomachs due to stress.[317]

Job stress is estimated to cost American companies more than $300 billion a year in health costs, absenteeism and poor performance. In addition, consider these statistics:

- 40% of job turnover results from stress.[318]

- Healthcare expenditures are nearly 50% greater for workers who report high levels of stress.[319]

- Replacing an employee costs an average of 120% to 200% of the affected position’s salary.[320]

- An estimated 60% of all job absenteeism is caused by stress.[321]

- Depression and unmanaged stress are the top two most costly risk factors in terms of medical expenditures. They increase health-care costs two to seven times more than physical risk factors such as smoking, obesity and poor exercise habits.[322]

- Employees who perceive they have little control over their jobs are nearly twice as likely to develop coronary heart disease as employees with high perceived job control.[323]

It also has become apparent that social incoherence not only influences the way we feel, relate and communicate with one another, it also affects physiological processes that directly affect health. Numerous studies have found that people undergoing social and cultural changes, or living in situations characterized by social disorganization, instability, isolation or disconnectedness, are at increased risk of acquiring many types of disease.[324-328] James Lynch provides a sobering statistic on the effects of social isolation on individuals. His research in social isolation shows that loneliness produces a greater risk for heart disease than smoking, obesity, lack of exercise and excessive alcohol consumption combined.[329]

On the other hand, there is an abundance of literature showing that close relationships and social networks are highly protective. Numerous studies of diverse populations, cultures, age groups and social strata have shown that individuals who are involved in close and meaningful relationships have significantly reduced mortality, reduced susceptibility to infectious and chronic disease, improved recovery from post-myocardial infarction and improved outcomes in pregnancy and childbirth.[330-332]

There are practical steps and practices that can be taken to build and stabilize organizational coherence and resilience. There are increasing numbers of hospitals, corporations, military units, schools and athletic teams, which are actively working towards increasing their team, group or organizational coherence. We have found that collective coherence is built by first working at the individual level. As individuals become more capable of self-management, the group increases its collective coherence and can achieve its objectives more effectively.

This section contains a summary of a few examples of organizations that have provided self-regulation skills combined with heart-rhythm coherence training. Overall, the results show improved workplace communication, satisfaction, productivity, lower healthcare costs, innovative problem-solving and reduced employee turnover, all of which can translate into a significant return on investment, not only financially, but also socially.

A number of hospitals that have implemented HeartMath training programs for their staff have seen increased personal, team and organizational benefits. The measures most often assessed are staff retention and employee satisfaction. For example, a study conducted at the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, Ariz. evaluated the personal and organizational effects of the HeartMath program on reducing stress and improving the health of oncology nurses (n = 29), and clinical managers (n = 15).[333]

The compelling imperative for the project was to find a positive and effective way to address the documented high stress levels of health-care workers and explore the impact of a positive coping approach on Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment-Revised (POQA-R) scores at baseline and seven months after the training program. Personal and organizational indicators of stress decreased in the expected directions in both groups.

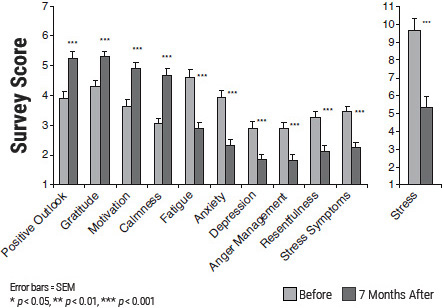

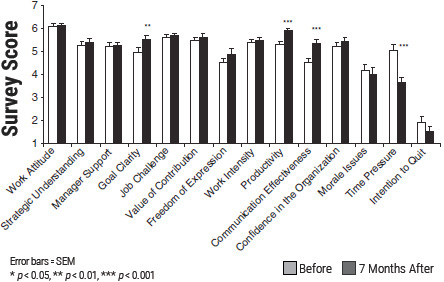

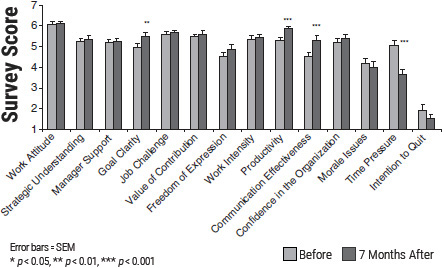

Figure 10.1 shows the results for the personal indicators of stress scales on the POQA-R for the oncology staff from pre-intervention to seven months postintervention. Statistically significant differences were found for each of the personal indicators (positive outlook, gratitude, motivation, calmness, fatigue, anxiety, depression, anger management, resentfulness and stress symptoms). Figure 10. 2 shows the results for the organizational indicators of stress factors on the POQA-R for the oncology staff. Although all of the indicators trended in the expected direction, statistically significant differences were found in the indicators of goal clarity (p < 0.01), productivity (p < 0.001), communication effectiveness (p < 0.001) and time pressure (p < 0.001). Turnover on the oncology unit was 13.12% pre-intervention and 9.8% seven months post-intervention. In addition, incremental time on the oncology unit dropped from 1.19 to 0.74 during the same time interval, and employee satisfaction survey scores for the unit increased in the following areas: confidence leadership was responding to issues/concerns; confidence the organization was taking genuine interest in employees’ well-being and showing a desire to continuously improve service on the unit; speaking their minds without fear; respect between physicians and allied health; and overall job satisfaction.

Figure 10.1 Oncology staff group, matched pairs analysis of personal indicators of stress from the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment, at baseline and seven months post-intervention.

Figure 10.2 Oncology staff group, matched pairs analysis of organizational scales from the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment, at baseline and seven months postintervention.

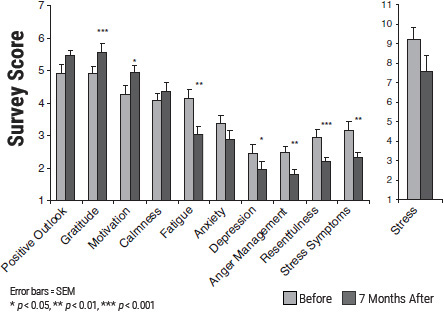

Figure 10.3 Leadership group, matched pairs analysis of personal indicators of stress from the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment, at baseline and seven months post-intervention.

Figure 10.4 Leadership group, matched pairs analysis of organizational scales from the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment, at baseline and seven months postintervention.

Figure 10.3 depicts the results of the POQA-R on the personal indicators of stress factors for the leadership group from pre-intervention to seven months post-intervention. Statistically significant differences were found in the personal indicators of gratitude (p < 0.001), fatigue (p < 0.01), depression (p < 0.05), anger management (p < 0.01), resentfulness (p < 0.001) and stress symptoms (p < 0.01). Figure 10.4 depicts the results of the organizational indicators of stress factors on the POQA-R for the leadership group. Statistically significant differences between baseline and seven months post-intervention were found on the indicators of manager support (p < 0.05) and value of contribution (p < 0.05).

The authors state that the findings from this study demonstrate stress and its symptoms are problematic issues for hospital and ambulatory clinic staff as evidenced by baseline measures of distress. Further, a workplace intervention was feasible and effective in promoting positive strategies for coping and enhancing well-being, personally and organizationally.

In a study conducted at the Fairfield Medical Center, a 222-bed community hospital in Lancaster, Ohio, a HeartMath workshop given in a series of six one-hour sessions, with one two-hour follow-up session was delivered to improve the well-being of hospital staff and physicians.[334] Special thought and consideration were given to being able to sustain the use of the selfregulation techniques over the long-term. As a result, strategies were developed to integrate the program into the hospital’s culture.

Four staff members from a variety of disciplines were selected to be certified in the HeartMath program to gain proficiency in methodology, practices and techniques. Two Workshops each week were offered from August 2007 through December 2010. A total of 975 employees, or 48% of the staff, participated. Sustainability of the program was aided by ensuring senior leadership support, management team training, use of techniques in committee and department meetings, consulting, classes to local educators and open workshops for employee family members.

Three metrics were selected to measure the success of the program: employee satisfaction, absenteeism rates and healthcare claims cost. Significant cultural and financial return on investment was demonstrated. Employees who received the HeartMath training experienced a 2:1 savings on health-care claims, compared to employees who had not received training. Employee opinion survey results demonstrated that employees who had HeartMath training had higher overall satisfaction scores than those who had not received training. HeartMath-trained participants demonstrated a lower overall absenteeism rate, resulting in a $94,794 savings over three years.

It was concluded that the HeartMath program and sustainability practices proved to be wise decisions and continue to be valuable when initiating new concepts in a stressful, changing environment. They highlighted the fact that sustainability was the key to long-term success and a true cultural change. Continued employee training of the HeartMath techniques and continued use of the tools enriches the program planning and implementation of new initiatives at Fairfield Medical Center.

In a study conducted by the National Health Service (NHS) a publicly funded health service in the United Kingdom that provides free point-of-use services for UK residents, the HeartMath Revitalizing Care Program was provided in workshops to four departments in an NHS trust from August to October 2011.[335] Participants included staff from three clinical wards and one reception area. Over a three-month period, 97 staff members participated in the workshops. Evaluation of the project was conducted using the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment – Revised 4 Scale (POQA-R4) as well as the pre- and post-training measures of staff turnover, absence rates and complaints.

The evaluation showed participants had demonstrated improvements in nine of the 10 personal qualities categories. These changes were statistically significant in eight areas, with fatigue and calmness showing the greatest improvements. It should be noted that the results of the pre- and post-comparison of staff turnover, sickness absence and complaints were inconclusive because of the short time frame of the study.

A study was conducted at Chesapeake Regional Medical Center (CRMC) in Virginia of 792 staff who completed pre-and post-measures with Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment (POQA) between February 2009 and December of 2010.[336] The intervention was a HeartMath workshop and training in Jean Watson’s Theory of Caring (Caritas processes). As a result of incorporating Caritas processes into the HeartMath workshop, the program development team at HeartMath created a workshop called "Revitalizing Care," which integrates the Caring Theory into the HeartMath concepts and tools. There were significant improvements in positive outlook, gratitude, motivation, calmness, and anger management as well as significant reductions in fatigue, anxiety, depression, resentfulness and physical symptoms of stress. The organizational scales showed significant improvements in strategic understanding, confidence in the organization, feeling valued, freedom of expression, communication, productivity and morale issues and a decrease in intention to quit.

Caring science theory and practices have been part of Kaiser Permanente’s strategic priority for the Kaiser Permanente Northern Region since 2010. Its goal is to ensure the continued spread across its medical centers of practices guided by a caring sciences framework that fosters caring-healing environments and that reinforce helping-trusting relationships between caregivers and patients. Kaiser staff were selected to become certified HeartMath trainers. There were four key elements in the trainer selection process: 1) Trainers were selected in contextual alignment with Kaiser’s strategic goals. 2) Leader/RN staff relationships were important. 3) Trainers had to be committed to advancing cultures of caring science and HeartMath. 4) The chief nursing officers who would become trainers had to emphasize consistent leadership support. During a 12-month period from June 2011 to June 2012, over 400 nurses, leaders and other support staff were trained in the program. Of those 400 participants, 263 completed both the pre- and post-POQA surveys.[337] Eight of the 14 scales showed statistically significant changes in work attitude, goal clarity, communication effectiveness, time pressure, intention to quit, strategic understanding and productivity. Improvements also were noted in well-being, quality of life, impacts on patient satisfaction, safety, and reduction of absenteeism. Additionally, benefits included improved relationships between nursing staff and leaders. The trainers reported being deeply affected on professional and personal levels.

“HeartMath’s programs have enabled our leaders to sustain peak performance, to manage more efficiently in a changing environment and to maintain work/life balance. For our staff, it has made the difference between required courtesy and genuine care.”

Other examples illustrating the effects of implementing the HeartMath self-regulation program come from the Cape Fear Valley Medical System in Cape Fear, North Carolina, which reduced nurse turnover from 24% to 13%; and Delnor Community Hospital in Chicago, which experienced a similar reduction, 27% to 14%, in addition to a dramatic improvement in employee satisfaction, results that have been sustained over a 10-year period. Similarly, the Duke University Health System reduced turnover in its emergency services division from 38% to 5%.

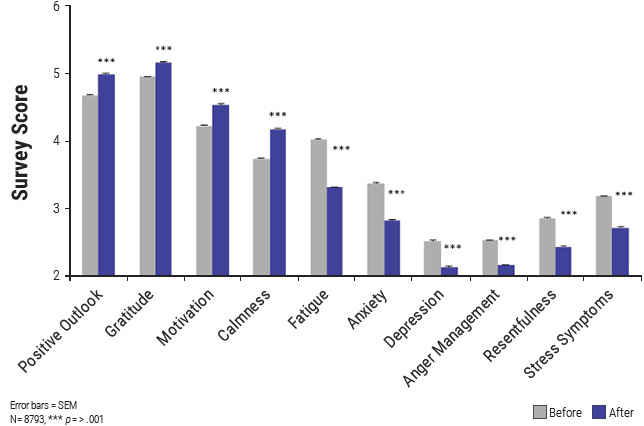

An analysis of the combined psychometric data from 8,793 health-care workers with matched pre- and post-POQA data collected before and six weeks after completion of a HeartMath self-regulation skills training program produced many positive results. Fatigue, anxiety, depression, anger and physical stress symptoms declined greatly, while positive outlook, gratitude, motivation and calmness improved significantly (Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.5 Shows matched pre- and post-data from the POQA from 8,793 health-care workers collected before and six weeks after completion of HeartMath training programs.

Studies In Law Enforcement Organizations

Several studies with police officers have found their capacity to recognize and self-regulate their responses to stressors in both work and personal contexts was significantly improved after learning the HeartMath self-regulation skills.

One study explored the nature and degree of physiological activation typically experienced by officers on the job and the effects of HeartMath’s Resilience Advantage training program on a group of police officers from Santa Clara County, California.[53] Areas assessed included vitality, emotional well-being, stress coping and interpersonal skills, work performance, workplace effectiveness and climate, family relationships, and physiological recalibration following acute stressors.

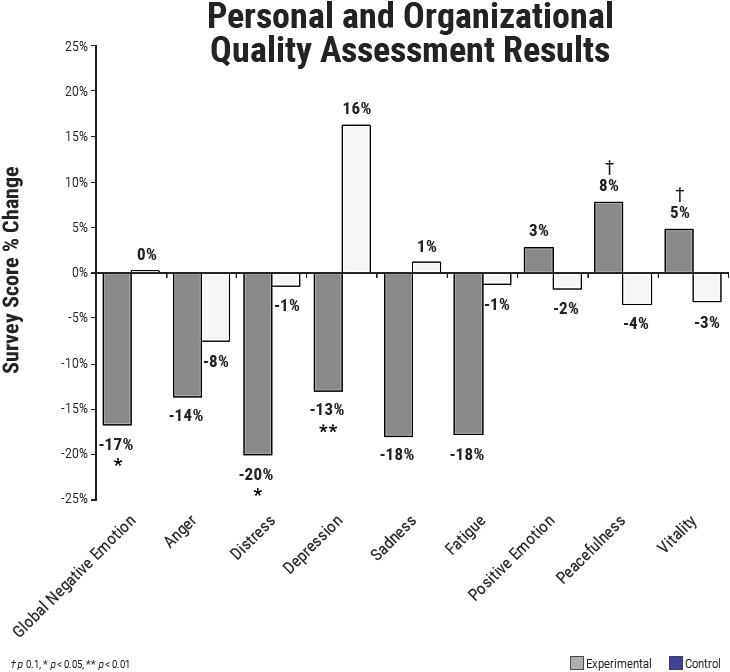

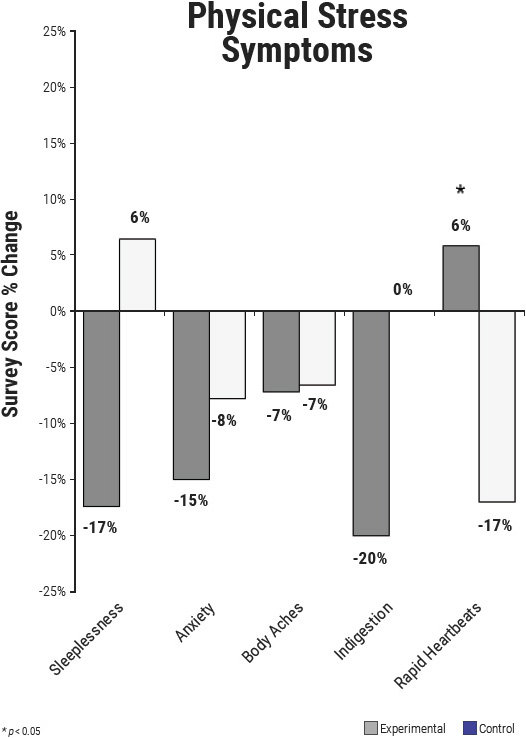

Physiological measurements were obtained to determine the real-time cardiovascular effects of acutely stressful situations encountered in highly realistic simulated police calls used in police training, and to identify officers at increased risk of future health challenges. The results showed that the resilience-building training improved officers’ capacity to recognize and self-regulate their responses to stressors in both work and personal contexts. Officers experienced significant reductions in stress, negative emotions and depression, compared to a control group, and increases in peacefulness and vitality, compared to the control group. (Figures 10.6 and 10.7). Improvements in family relationships, more effective communication and cooperation within work teams, and enhanced work performance also were noted.

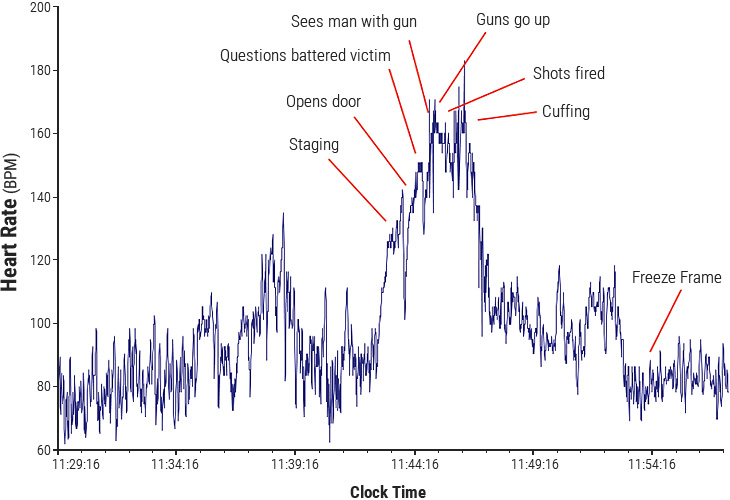

Heart-rate and blood-pressure measurements taken during simulated police-call scenarios showed that acutely stressful circumstances typically encountered on the job resulted in a tremendous degree of physiological activation, from which it took a considerable amount of time to recover (Figure 10.8). Autonomic nervous system assessments based on heart rate variability analysis of 24-hour ECG recordings revealed that 11% of the officers were at higher risk, which was more than twice the percentage typically found in the general population.

Figure 10.6 Improvements in stress and emotional well-being. Compares the differences between the average pre- and post-training scores for each variable as measured by the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment. Compared to the control group, participants trained in the Resilience Advantage program exhibited significant reductions in distress, depression and global negative emotion, and increases in peacefulness and vitality. The global negative emotion score is the overall average of the individual scores for the anger, distress, depression and sadness constructs. Note that the control group experienced a marked rise in depression over the same time period. †p < .1, * p < .05, ** p < .01.

Figure 10.7 Changes in physical stress symptoms. Shows the changes in five physical symptoms of stress for all participants at the start of the study and 16 weeks later (four weeks after completion of the training).

Figure 10.8 This graph provides a typical example of the ability of an officer from the experimental group to shift and reset after a domestic violence scenario. Note that when the scenario ends, the officer’s heart rate initially falls, but remains elevated in a range above the normal baseline When this officer used the Freeze Frame Technique, there was an immediate, further reduction in the heart rate back to baseline. In pre-training scenarios it took on average, 1 hour and 5 minutes before returning to baseline values.

Key Benefits of the HeartMath Training for Police Officers*

- Increased awareness and self-management of stress reactions.

- Greater confidence, balance and clarity under acute stress.

- Quicker physiological and psychological recalibration following acute stress.

- Improved work performance.

- Reduced competition, improved communication and greater cooperation within work teams.

- Reduced distress, anger, sadness and fatigue.

- Reduced sleeplessness and physical stress symptoms.

- Increased peacefulness and vitality.

- Improved listening and relationships with family.

*Compiled from the results of psychological and performance assessments, and a semi-structured interview conducted post-training.

A study was conducted with 10 male and four female police officers and two dispatchers with the San Diego Police Department. It included self-regulation skills training comprising an introductory two-hour training session, and telephone mentoring sessions spread over a four-week period by experienced HeartMath mentors. In addition, the officers were issued an iPad app called Stress Resilience Training System (SRTS), which includes training modules on stress and its effects, HRV coherence biofeedback, a series of HeartMath self-regulation techniques and HRVcontrolled games.

Outcome measures were the Personal and Organizational Quality Assessment (POQA) survey, the mentors’ reports of their observations and records of participants’ comments from the mentoring sessions. The POQA results were overwhelmingly positive: All four main scales showed improvement, including emotional vitality, up 25% (p = 0.05), and physical stress, up 24% (p = 0.01). Eight of the nine subscales showed improvement, with the stress subscale improving approximately 40% (p = 0.06). Participant responses also were uniformly positive and enthusiastic. Individual participants praised the program and related improvements in both on-the-job performance and personal and familial situations.[193]

Fighter Pilot Study

A study of 41 fighter pilots engaging in flight simulator tasks to better understand pilots’ workload and visual attention in the cockpit while conducting a simulated air-to-air tactic operations found a significant correlation between higher levels of performance and heart-rhythm coherence as well as lower levels of frustration. The study also found that the objective measurement of workload and attention distribution, as reflected in HRV coherence and eye-tracking, provided more reliable indicators than self-report approaches and that HRV coherence scores of expert pilots and novice pilots were significantly different.[191]

HeartMath in a Prison Environment

A study conducted by Lori Bosteder and Sara Hargrave in the Coffee Creek Women’s Correctional Facility, in Wilsonville, Ore. sought to determine whether emotional intelligence training would help female inmates better manage the emotional difficulties of living and learning within a prison environment.[338] Many of the women who enter prison have difficulty in emotion self-management and positive social engagement. They often come from dysfunctional or abusive backgrounds, and many have become accustomed to abusing drugs and/or alcohol as a means of coping with distressing emotions. The highly charged emotional environment of a women’s prison is augmented by the inherent struggles of prison life, including the loss of most freedoms and nearly all privacy. This emotional chaos frequently impairs inmates’ ability to learn and acquire new skills in prison work-based education programs, and may also deter their successful transition back into society.

The study participants were 17 women in minimum security. These women were all students of the prison’s 18-month work-based education program in computer technology. Over a 10-week period, the women participated in three workshops that focused on basic emotional intelligence concepts and skills in the areas of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management. HeartMath material, practice of its tools and heart-rhythm coherence feedback were the major focus of the training. Participants read and completed self-reflective exercises in HeartMath’s Transforming Stress, Transforming Anxiety and Transforming Anger books. Practice of the Neutral and Heart Lock-In self-regulation techniques was integrated into the daily classes, as was heartrhythm coherence feedback training with handheld emWave devices. Each woman also received individualized coaching and training in HeartMath emotionmanagement tools and use of the heart-rhythm feedback technology. The outcome measures used in the study were the Emotional Intelligence Appraisal-ME, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) self-report survey, discipline reports for the participants that were recorded by correctional officers four months before the training and four months after. In addition, observation notes over the 10-week study period were recorded by the computer technology class instructor, who noted student comments and any changes in their behaviors and interactions as they practiced the emotional awareness and self-management skills. Also, each participant’s extensive evaluation at the end of the study provided both quantitative and qualitative data on her experiences in the program.

Analysis of the pre- and post-data showed significant reductions in symptoms of emotional distress, obsessive- compulsive patterns, depression and anxiety on the BSI, and significant increases in self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and relationship management on the Emotional Intelligence Appraisal scales. The discipline reports showed a significant decrease in discipline problems outside the classroom.

Qualitative data also supported the program’s effectiveness. Most participants reported in their evaluations significant benefits to themselves and their social relationships. A few reported an initial increase in depression and anxiety as a result of feeling for the first time in years, but they improved with support from the instructor. The computer technology course instructor observed major improvement in the learning environment and growth in her students’ ability to self-regulate and get along with others. Two students who were paroled after the study contacted the trainers and reported that they were using the HeartMath skills to manage the struggles they were facing on the outside and that they were creating better outcomes for themselves than they would have in the past.

The researchers observed that crucial factors in the program’s success were a supportive group and the consistent support and encouragement provided by the course instructor as students experienced the initial disorientation created by the psychological changes resulting from their emotion-management practice. Because the group met daily during the week, a classroom setting worked well to provide this close attention and support. The program led to important psychosocial improvements in the participants over a relatively brief period of time and appeared to significantly enhance inmates’ capacity to learn within the prison setting and to eventually successfully reintegrate into society.